Hello ladies and gents this is the Viking telling you that today we are talking about

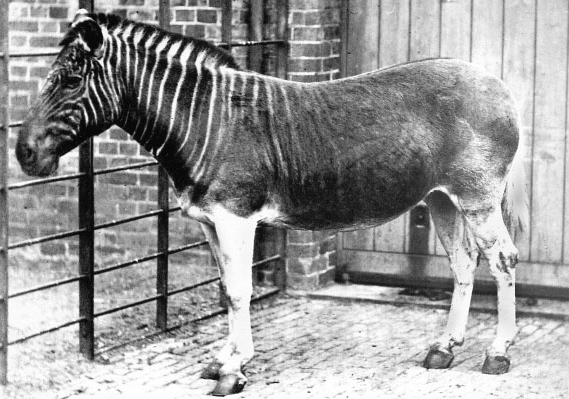

QUAGGA

As it was easy to find and kill, the quagga was hunted by early Dutch settlers and later by Afrikaners to provide meat or for their skins. The skins were traded or used locally. The quagga was probably vulnerable to extinction due to its limited distribution, and it may have competed with domestic livestock for forage. The quagga had disappeared from much of its range by the 1850s. The last population in the wild, in the Orange Free State, was extirpated in the late 1870, The last known wild quagga died in 1878.

Quaggas were captured and shipped to Europe, where they were displayed in zoos. Lord Morton tried to save the animal from extinction by starting a captive-breeding programme. He was only able to obtain a single male, which in desperation he bred with a female horse. This produced a female hybrid with zebra stripes on its back and legs.

Lord Morton's mare was sold and was subsequently bred with a black stallion, resulting in offspring that again had zebra stripes. An account of this was published in 1820 by the Royal Society. This led to new ideas on telegony, referred to as pangenesis by Charles Darwin. At the close of the 19th century, the Scottish zoologist James Cossar Ewart argued against these ideas and proved, with several cross-breeding experiments, that zebra stripes can pop up as an atavistic trait at any time.

The quagga was long regarded a suitable candidate for domestication, as it counted as the most docile of the striped horses. The earliest Dutch colonists in South Africa had already fantasized about this possibility, because their imported work horses did not perform very well in the extreme climate and regularly fell prey to the feared African horse sickness.

In 1843, the English naturalist Charles Hamilton Smith wrote that the quagga was 'unquestionably best calculated for domestication, both as regards strength and docility'. Only a few descriptions have been given of tame or domesticated quaggas in South Africa. In Europe, the only confirmed cases are two stallions driven in a phaeton by Joseph Wilfred Parkins, sheriff of London in 1819–1820, and the quaggas and their hybrid offspring of London Zoo, which were used to pull a cart and transport vegetables from the market to the zoo.

Nevertheless, the reveries continued long after the death of the last quagga in 1883. In 1889, the naturalist Henry Bryden wrote: "That an animal so beautiful, so capable of domestication and use, and to be found not long since in so great abundance, should have been allowed to be swept from the face of the earth, is surely a disgrace to our latter-day civilization."

The specimen in London died in 1872 and the one in Berlin in 1875. The last captive quagga, a female in Amsterdam's Natura Artis Magistra zoo, lived there from 9 May 1867 until it died on 12 August 1883, but its origin and cause of death are unclear. Its death was not recognised as signifying the extinction of its kind at the time, and the zoo requested another specimen; hunters believed it could still be found "closer to the interior" in the Cape Colony.

Since locals used the term quagga to refer to all zebras, this may have led to the confusion. The extinction of the quagga was internationally accepted by the 1900 Convention for the Preservation of Wild Animals, Birds and Fish in Africa. The last specimen was featured on a Dutch stamp in 1988. There are 23 known stuffed and mounted quagga specimens throughout the world, including a juvenile, two foals, and a foetus. In addition, a mounted head and neck, a foot, seven complete skeletons, and samples of various tissues remain. A 24th mounted specimen was destroyed in Königsberg, Germany, during World War II, and various skeletons and bones have also been lost.

And as always have a chilled day from the Viking

Comments

Post a Comment