Hello ladies and gents this is the Viking telling you that today we are talking about

What is dementia?

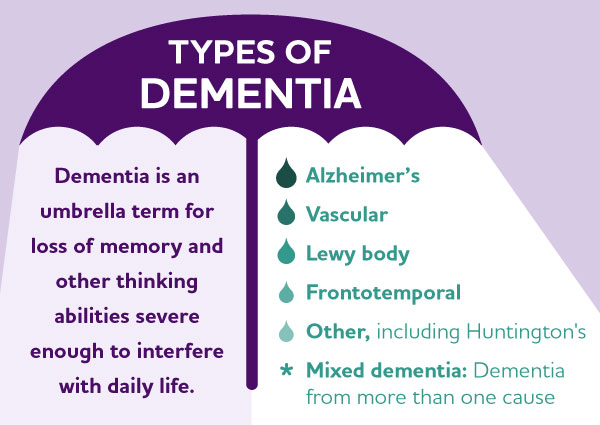

Dementia is caused when the brain is damaged by diseases. It is progressive, meaning the symptoms will eventually get worse, and current treatments are limited and only suitable for certain types of dementia. The word is an umbrella term covering many different types of the condition – and while experts don’t have an exact figure of how many there are, it’s estimated to be over 100.

Dementia can affect anyone, whatever their gender, ethnic group, class, educational or professional background, and there is no cure, although research is ongoing.

Many people living with dementia, and indeed people not living with dementia, register for Join Dementia Research to contribute towards understanding of dementia, support the discovery of new treatments and help in working towards a cure.

Types of dementia

When your loved one is diagnosed with dementia, the diagnosing clinician should be able to tell your loved one what type they have. This is useful to know since symptoms and patterns of progression vary from one to another, and it may help you and your loved one feel more prepared for what the future holds.

Some of the most prominent types of dementia are:

Alzheimer’s disease

– Alzheimer’s disease is the most common type of dementia, affecting multiple brain functions

– Early damage in Alzheimer’s usually affects a part of the brain called the hippocampus, which stores our day-to-day memory

– This means the first sign of Alzheimer’s disease is usually problems with memory, such as forgetting a conversation or the names of places or people

– As the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease often progress slowly, it can be hard to spot, and people may think they’re just a part of getting older

Vascular dementia

– Vascular dementia is the second most common type of dementia, affecting around 150,000 people in the UK

– Around 20% of people who have a stroke develop vascular dementia

– ‘Mini strokes’, also known as a TIAs (Transient Ischemic Attacks), may also be responsible

– Vascular dementia is fairly well understood, thanks to the huge amount of research that has gone into understanding how to keep the vascular system (the heart and blood system) in good health. This illustrates why risk-reduction advice often tells us that what’s good for the heart is good for the head

Dementia with Lewy bodies

– Around 10-15% of people with dementia have dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB)

– DLB is a type of dementia that shares symptoms with both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, and can often be wrongly diagnosed as Alzheimer’s

– People with DLB frequently experience sleep disturbances that may begin years before they are diagnosed

– Visual hallucinations are also very common, and problems with movement, similar to those experienced by people with Parkinson’s, affect around two-thirds of people by the time they are diagnosed with DLB, putting the person more at risk of a fall

Frontotemporal dementia

– Frontotemporal dementia is a less common type of dementia. It is sometimes called Pick’s disease or frontal lobe dementia

– It is a significant cause of dementia in people under 65 years, and is often diagnosed between 45 and 65 years of age

– People with frontotemporal dementia experience changes in personality, behaviour and language, but memory is less affected

Mixed dementia

– Many people believe that a person can only have one type of dementia at the same time, but around 10% of people are diagnosed with mixed dementia

– Mixed dementia is, most commonly, a combination of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia, and, less commonly, Alzheimer’s and dementia with Lewy bodies

Dementia in younger people

People with dementia whose symptoms started before they were 65 are described as having ‘younger-onset dementia’. There are estimated to be at least 42,000 people living with this kind of dementia in the UK.

The symptoms of dementia may be similar regardless of a person’s age, but younger people often have different needs – they may, for example still be working when they’re diagnosed – and therefore require age-appropriate support.

Dementia in a younger person can progress more rapidly, although this may be partly down to our perceptions – if your loved one has found it more difficult to get a timely diagnosis due to their age, their dementia may have significantly progressed by the time they are eventually diagnosed with dementia.

Comments

Post a Comment